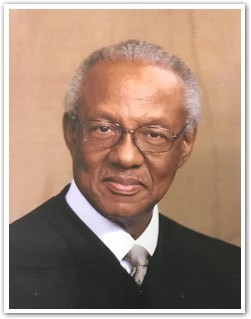

At the end of the month, 30th Judicial District Chancellor Walter L. Evans will retire after 22 years serving the people of Shelby County in Chancery Court.

The retirement caps off a long and successful career that saw Chancellor Evans spend over two decades in private legal practice before becoming a municipal judge for the City of Memphis and then stepping up to the Chancery Court bench.

A graduate of Howard University and then the Howard University School of Law, Chancellor Evans is also a veteran, having served two years in the military, one of them in Vietnam, following law school. Upon completion of his military service, Chancellor Evans earned an LLM from Harvard Law School in 1971.

Chancellor Evans’ career is winding down in the same city where his story began: his hometown of Memphis.

While Chancellor Evans was still young, his father passed away at an early age. His mother was employed in a private home and helped instill in him the value of hard work. Chancellor Evans held a steady job throughout high school painting signs for a local grocery store. That job would help decide his undergraduate course of study a few years later.

“I was an artist, or at least had artistic talent,” he said. “That along with my good grades in math persuaded me to pursue an architecture degree.”

The hard work continued after he graduated from Melrose High School in 1960 and moved to Washington, D.C. to attend Howard University. Upon arrival, he discovered that an architecture degree required five years rather than four years of study.

“I really didn’t know how I could make it in a five-year-course because my mother was not able to provide any income for me, and the only way I was able to make it through college was based on scholarships, loans, and working,” Chancellor Evans recalled.

Despite the economic hardship, Chancellor Evans stuck it out, working a variety of on-campus jobs during his spare time to supplement his ROTC scholarship. He thrived in both academics and extracurricular activities and was named president of both the School of Engineering and Architecture student council and of his fraternity, Alpha Phi Alpha. One particularly memorable experience from college is when he was selected to attend a dinner for student leaders at the White House. Chancellor Evans remembers being greeted warmly by President Lyndon B. Johnson.

While he enjoyed architecture, over the course of his undergraduate studies, Chancellor Evans became increasingly intrigued by a different subject altogether: the law.

“I realized that a career in architecture was very limited and a career in law offered more alternative opportunities for employment,” he said. “Because I was able to receive a scholarship from the law school there was an incentive for me to pursue a career in law.”

Chancellor Evans went straight to Howard University School of Law after receiving his undergraduate degree and earned his Juris Doctor in 1968. Thereafter, he went on active duty in the United States Army, where he served as a prosecuting attorney stationed in the United States for his first year. In his second year of service he was shipped to Vietnam where he served as an attorney in the United States Army Corps of Engineers. He finished his military service with the rank of Captain.

While in Vietnam, Chancellor Evans began applying to various law schools to further his studies with a Master of Laws degree. He received a Ford Foundation scholarship to attend Harvard Law School, where he found himself one of the few African American students in his class. He earned an LLM in 1971, with a focus in Urban Law.

During his time at Harvard, Chancellor Evans received an invitation from Memphis attorney George Brown to come home and work with him at Memphis Area Legal Services. As Chancellor Evans explained, legal aid organizations and other entities that received government funding were often the only places African American attorneys could find work in that era.

“A lot of the white law firms would not hire Black attorneys,” Chancellor Evans said. “The Black attorneys had to opt for positions with legal services and the public defender’s office.”

Chancellor Evans and Brown left Legal Services after a few years and started their own firm, Brown & Evans. As an African American attorney in Memphis at that time, Chancellor Evans followed in the footsteps of men like Benjamin Hooks, A.W. Willis, Jr., and Russell Sugarmon, whose careers were forged in the early years of the Civil Rights Era.

“They were pioneering Black attorneys,” Chancellor Evans said.

Brown & Evans handled whatever types of cases came through the door, basically.

“I didn’t have the option of specializing in a particular area of the law,” Chancellor Evans said. “Real estate closings, wills, traffic violations, breach of contract matters; you name it, everything that came through the door that was income producing.”

The high point in his private practice came in 1979, when Chancellor Evans argued and won a habeas corpus case, Parker v. Randolph, before the Supreme Court of the United States.

“Lawyers from all over the country wanted me to turn the case over to them, and I told them no way because very few opportunities come when a lawyer gets to personally argue before the United States Supreme Court,” Chancellor Evans said. “It was a very memorable occasion.”

An audio recording of the oral arguments before the United States Supreme Court can be found here.

In 1980, George Brown became the first African American justice on the Tennessee Supreme Court when he was appointed to that position by Governor Lamar Alexander. He would subsequently lose election to that seat, but would become a long-serving circuit court judge.

Chancellor Evans formed a new firm, Evans & Kyle, shortly after Brown left to begin his judicial career. Chancellor Evans was senior partner in that firm, which also employed future 30th Judicial District Circuit Court Judge Rita Stotts.

Chancellor Evans stayed with that firm until 1994, when a new opportunity arose. City of Memphis Mayor Willie Herenton approached him and asked if he would be interested in becoming a municipal judge. At first, Chancellor Evans was not sure if he was interested. He enjoyed his career as an attorney. But after thinking it over and gathering input from his family and Judge Brown, he accepted.

Chancellor Evans took to the new job immediately.

“Because I had handled so many different types of cases, I felt I was able to transition into being a judge without much difficulty,” he said. By that time, he had seen a lot of judges in actions, too, having argued in practically every level of the judicial system.

After four years of dealing with traffic violations and other minor cases that were easily disposed of, Chancellor Evans decided to attempt another career change.

“I wanted something more challenging,” he said.

He chose to run against longtime incumbent Chancellor Neal Small in the 1998 election.

“I decided I’d give it a shot,” Chancellor Evans said. “I was fortunate enough to win.”

Chancellor Evans soon found that he enjoyed the added responsibility and complexity that came with chancery court cases.

“As a judge of the Chancery Court I was able to make rulings and decisions based on what I felt to be equitable and just,” he said. “Most of the cases in Chancery Court are not jury cases. The judge has to make decisions based on his determination as to whether it’s fair or equitable.”

Chancellor Evans has presided over numerous high-profile cases during his tenure on the court, including cases involving FedEx, the Memphis Grizzlies NBA team, and Shelby County Juvenile Court.

No matter the case, Chancellor Evans has always followed the same guideline.

“Listen and try to be as fair and equitable as possible,” he said.

This means that Chancellor Evans never based decisions on what he thought appellate courts would do.

“They make mistakes just like we make mistakes,” he said.

And while he has always tried his best to make the right decisions, a central aspect of his judicial philosophy is humility.

“One thing I know is no judge knows everything,” he said. “And no lawyer knows everything.” That is why good arguments are so necessary. They can persuade when difficult matters are in play.

Outside of the courtroom, Chancellor Evans is a stalwart member of Magnolia First Baptist Church. His mother would take him there when he was a child, and he has been going ever since. His step-grandfather was one of the church's three founders.

He has been married to his wife, Elise, since 1973. They have two adult children, Jonathan Christian Evans, an information technology specialist, and Walter Evans, II, an attorney in Shelby County.

Looking back at his life and long career, hard work and all, Chancellor Evans ultimately ascribes his success to one thing.

“The good Lord has been with me all the way,” he said. “That’s all I can say.”