Once a month at Room in the Inn, a homeless services organization in Nashville, criminal defendants with needs most people never have to worry about enter a room on the second floor seeking relief. The defendants are all homeless, and most of them have recently been arrested on charges directly related to their homelessness: trespassing for taking shelter in a doorway, for instance, or public intoxication because they have no private space.

They come to Room in the Inn to participate in the Homeless Court docket, an innovative program designed to connect people experiencing homelessness with local service providers and to keep them from compiling a criminal record that can jeopardize their ability to gain a foothold in the job market and establish permanent housing.

The Homeless Court in Nashville is based on a similar program that the Baker Donelson law firm helped to launch in New Orleans in 2010. Baker Donelson has shown a commitment to tackling the problem of homelessness over the years through such efforts as coordinating the Homeless Experience Legal Protection Clinic in cities around the country, including Nashville. After the firm decided in the fall of 2019 to expand the court into Nashville, they reached out to Metropolitan Nashville and Davidson County General Sessions Court Judge Lynda Jones to help put it together and preside over it. She agreed and met with various stakeholders, including the Office of the District Attorney and the Metropolitan Public Defender’s Office, to make it happen.

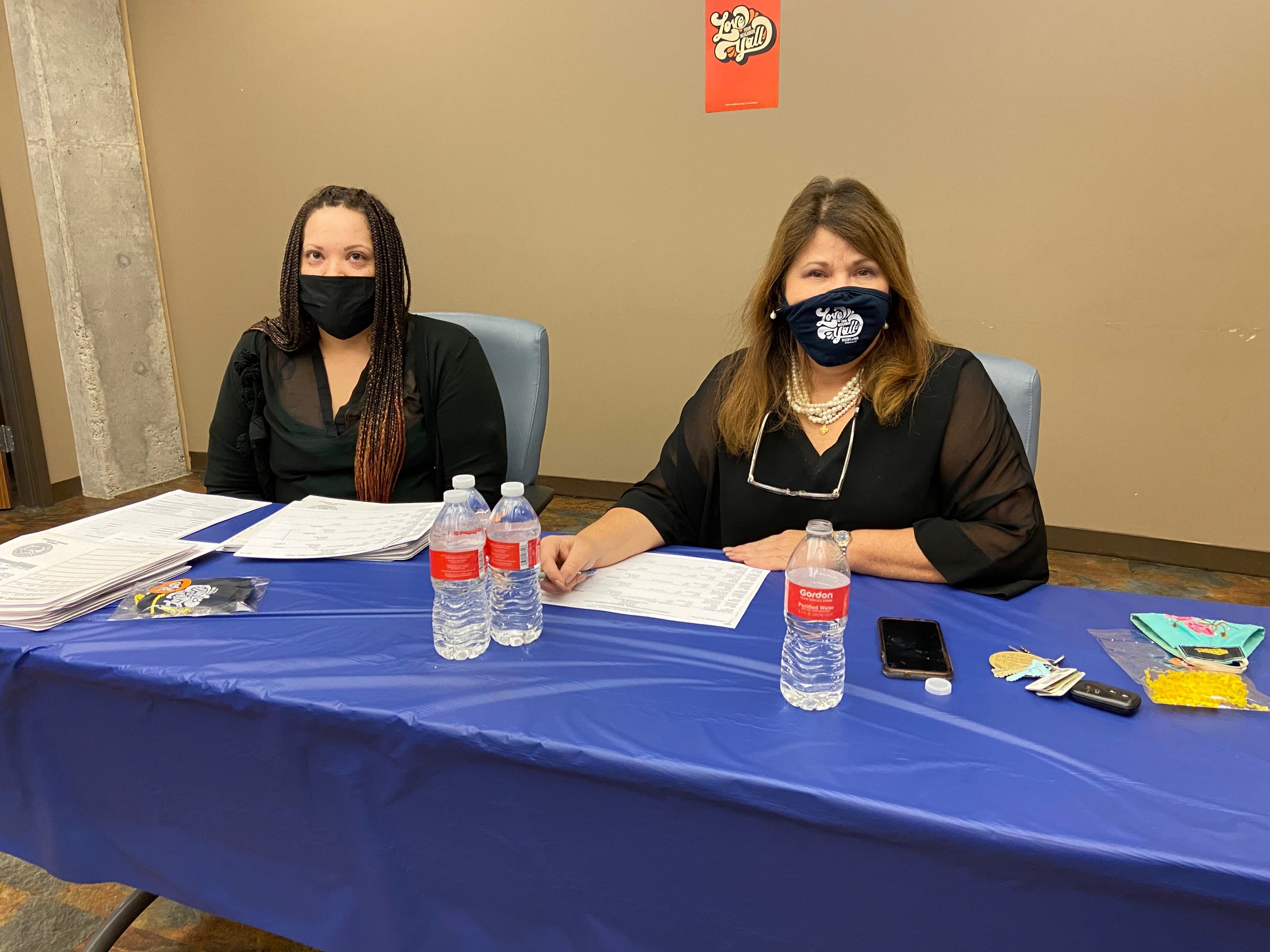

Fast forward one year and a masked Judge Jones sat in a socially distanced makeshift courtroom at Room in the Inn as the November session of Nashville’s Homeless Court, its third, got underway.

“How are you doing today?” Judge Jones asked as a woman entered the room and stood by Public Defender Joan Lawson. Assistant District Attorney Emily Todoran sat at an adjoining table.

Judge Jones informed the woman that the district attorney’s office had reached an agreement with Lawson to dismiss her case. Indeed, all dismissals in Homeless Court are contingent on an agreement between the district attorney and the public defender.

“It’s cold outside. We have a small gift for you,” Judge Jones said, handing the woman a bag containing a hat and gloves.

The woman then left the room to meet with a case worker from Room in the Inn.

This sequence of events, lasting just a couple of minutes, was repeated four more times that Friday. The final client, a man wearing a Scottie Pippen basketball jersey, was delayed in getting there because he missed his bus, a lack of transportation being just one of many obstacles that homeless people face in trying to reach service providers.

While five clients may not seem like a lot, word about the court is getting around with district attorneys and public defenders, Todoran said.

Judge Jones is happy that this session featured the Court’s first female clients.

“Three of the women on the docket today brought friends with them who need services,” she said. “They are getting connected before they get into the criminal justice system, so they may not ever come into contact with the criminal justice system. That is a big thing that we did not anticipate, which is wonderful.”

The purpose of the court is two-fold. It is “to remove legal barriers to housing and employment for people who are homeless and then to connect our participants with service providers in town,” Hannah Cole, an associate with Baker Donelson who was also present at Homeless Court, said.

The first purpose is inextricably linked with the criminal charges that the participants face.

“We don’t want people to have convictions in every situation,” Todoran said. “So if there’s a way we can treat a person and handle a case so that a conviction isn’t necessary we’re happy to do that because we understand there are so many collateral negative consequences from having a conviction. This program that Judge Jones started gives us another opportunity to help people avoid these convictions.”

Lawson noted some of those negative consequences.

“A criminal conviction could prevent you from getting subsidized housing, could prevent you from getting loans for education, could prevent you from getting a job,” she said. “Even some halfway houses won’t take you” if you have a criminal conviction.

While most of the people in Homeless Court are there on charges related to “the crime of being homeless,” as Cole put it, there is no hard and fast set of crimes that render people eligible for the court. Even some people who have been charged with felonies have had their charges dismissed. Every person’s individual situation is examined on a case-by-case basis.

For instance, one of the felony charges came about because a person had been picked up for a separate non-felony charge and then was found to be in possession of a crack pipe once he got to jail.

“We figured he’d be better off connected with services than having a conviction or staying in jail,” Todoran said. “Neither of those things are going to help him, and the community doesn’t benefit if he has a conviction for probably accidentally bringing a crack pipe in.”

So far, no one who has appeared in Homeless Court has been rearrested after having charges dismissed.

The dismissal of charges is not the end of the Homeless Court’s project, though, but the beginning of it. After appearing before Judge Jones, court participants meet with a member of Room in the Inn’s staff. These staff members listen to the participants’ personal stories and try to determine how best they can be helped.

“What we find is typically people have a whole constellation of challenges and goals, so we try to really holistically just have a conversation with them, ask them about some key areas that may be of concern, their most urgent needs,” Stephen Wilder, a manager in the Room in the Inn’s residential community, said.

As an example, Wilder talked about the issues that one court participant was currently facing. He did not have a birth certificate, leaving him with only one form of ID. A lot of housing or employment applications require two forms of identification, Wilder said, so they were going to help the man obtain a birth certificate. Wilder also discovered that this man was a military veteran who was not connected with some benefits that he should be eligible for. In addition, Wilder discussed employment resources with the man and spoke with him about setting up an appointment with a primary care doctor. The man had not been to a doctor in some time.

“That’s a good example,” Wilder said. “It’s not just one thing that’s going to be a barrier for someone. We try to approach the whole person and give them the resources they need to pursue lot of different ways of moving forward.”

Lawson said she had a previous client whose home was destroyed by a tornado. She had no driver’s license and no social security card.

“She could get help, but she doesn’t know where to go or who to ask,” she said. “By coming here we can help fill in some of those gaps and find out what is it you need so we can help you.”

Help is particularly important because the process of getting a new driver’s license or birth certificate can be time-consuming and difficult even for someone who is not homeless.

“If you don’t have a phone or a car it makes it that much harder to figure out how to do that,” Lawson said. That can be especially true if you are missing multiple documents. To get a new driver’s license, for example, you need to present some form of proof of identity, like a birth certificate.

While the work of the Homeless Court fulfills an important societal and criminal justice function, it is also rewarding to those who help run it.

“It just personally makes me happy to see,” Todoran said. “Anytime something positive can happen in the criminal justice system it just really makes me happy.”

Judge Jones said that she too enjoys presiding over the docket and seeing people take the first steps to getting their lives back on track.

“I think it shows the power of collaboration in combining city resources, private resources, and nonprofit resources to make our entire city a better place to live and to lift people up who are often forgotten,” she said.